But there were also economic reasons. Especially in Norrland, many smaller forest owners felt heavily pressured by the companies. Timber measurement became particularly controversial. Measuring the cubic content of a log is difficult. It’s round, it tapers, but not all trees grow in the same way. There were templates for how to measure, but also a lot of arbitrariness. Initially, it was the buyers who did the measuring, and the forest owners looked at the settlements with great distrust.

The 1920s crisis spurred development. When the inflation boom turned into sharp deflation, the economy collapsed. The sawmills were under pressure and tried to survive the crisis by lowering the price of saw logs. The cooperative associations beckoned to the farmers as a way to fight back and secure better conditions.

Preparedness for fuel supply became the forest owners' movement's breakthrough. When World War II broke out, the state organized wood management to avoid the hardships of World War I. The forest owner associations were ready to deliver to the state crisis authorities. The generous economic conditions meant that the forest owner associations gained the financial strength that served well in their dealings after the war.

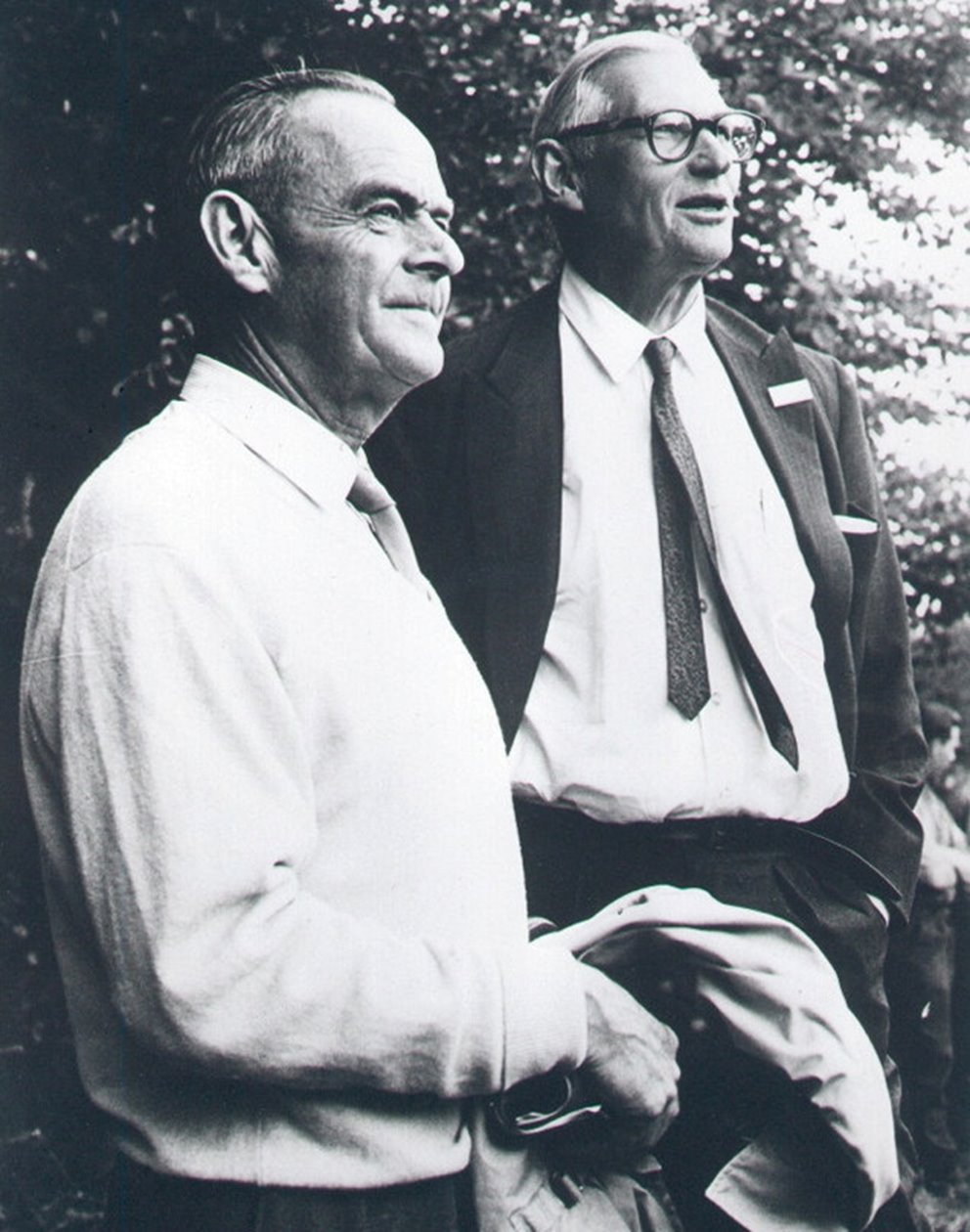

Gösta Edström and Södra

In Småland, forest owners in several counties formed associations. In the spring of 1935, Blekinge and southern Kalmar County joined Kronoberg for a joint headquarters in Växjö. The forester Gösta Edström was appointed business leader. Gradually, more associations joined, until today's Södra was established.

Thanks to the profits from WWII firewood, the federation began buying its own industries in the 1940s. Its first own factory was founded in 1940, when the association built a tar kiln in Lenhovda. After a storm swept southern and central Sweden in 1943, they started buying and building their own sawmills to ease the pressure.

In January 1950, the government commissioned an inquiry into southern Sweden's forest industries, where Edström became a member. The investigation showed that there was a surplus of sulfate wood in southeastern Sweden. Then the forest owners decided to invest in a pulp mill in Mönsterås in 1957.

Södra vs Wallenberg

In the wake of the 1950s investigation, the Wallenberg family also became interested in southern Sweden. This led to a sharp conflict when Södra was about to build its second pulp mill.

Where should the mill be located? Both Södra and Marcus Wallenberg j.r. eyed the Mörrum River in Blekinge. The river mouth is located a few kilometers west of Karlshamn, and it was believed that the Baltic Sea could handle the emissions. After a bidding war, Södra acquired the land needed, while Wallenberg built Nymölla by the Skräbe River in eastern Skåne.

In choosing the manufacturing method, Wallenbergers opted for the completely untested magnefit process. It had the advantage of being able to use beech wood, which forest owners in Skåne and Blekinge had difficulty finding a market for, but it came with long-lasting start-up problems.

The success with Mörrum strengthened Edström's reputation within the forest owners' movement. At the inauguration, neighboring associations decided to merge into Södra. Shortly thereafter, the decision was made to build Värö, so that the forest owners would have factories in the east, south, and west. The mill was inaugurated in 1972. Both Mönsterås and Värö were later complemented with large sawmills, so that they became efficient forest complexes.

1970s Steel Bath

During the 1970s, the collapse came. OPEC countries' increases in oil prices in 1973 initially benefited raw material producers like the forest industry, but then oil eroded international demand. Södra had overbought during the good years and acquired many small sawmills and mills that were difficult to modernize.

The sharp wage increases in the mid-1970s broke the margins for most of Södra's units. The adjustment was complicated by the fact that many of the federation's most active members were also local politicians who resisted necessary closures.

Södra was forced to turn to the state, which became a co-owner of the federation's industry part. The sister company NCB in Norrland – Gunnar Hedlund's creation – disappeared, but Södra acquired the right to buy back the state's shares. The forest owners in the south did not want to lose the three large pulp mills and the modern sawmills.

During the state's time as a co-owner, the builder Göran Ekelund was appointed CEO of Södra's industries. Several of the painful closures were pushed through. Södra got back on its feet, members paid their contributions in advance, and the association could buy out the state. Södra survived the crisis.

The storm Gudrun

During the 20th century, the recurring storms have become the greatest threat to forest owners. Prices are pushed to the bottom, and the risk of insect attacks increases considerably.

Therefore, the hurricane Gudrun on January 8-9, 2005, could have become an economic catastrophe. The morning after the hurricane weekend, fortune hunters began calling. They offered desperate forest owners to transport the storm-felled timber for free … they simply planned to get the timber cheaply for their own benefit.

Never had cooperation been more useful. Södra made quick decisions that saved the situation for forest owners. Many were still hit hard, but the outcome would have been even worse without cooperation.

Diversity Through Cooperation

Cooperation has become a breath of fresh air for the diversity of silviculture. Every farmer has been able to cultivate according to their own head and still find a market for their timber on fair terms.

One of the forest owner associations' most important contributions has been the forestry areas. By the farmers in a district joining together, they could share the costs of mechanization when this took off in earnest during the 1960s.

Many first thought that only the large companies would afford the new expensive machines. Through the forestry areas, they became available even to the forest farmers – as much and as little as they wanted. The areas became a flexible way to adapt to each farmer’s wishes for how they wanted to manage their forest.

The hundreds of thousands of private forest owners manage their forests in many different ways. The strength of cooperation has made it possible for more than otherwise to make their own decisions. The state and market have tried to influence through environmental support and certification, but individual forest owners have been able to set aside rigid regulations and go their own way.